I was hoping to have a nice relaxing end to a difficult week, but Standard and Poor’s has officially downgraded the United States’ credit rating to AA+. And of course, they did it when the markets are closed for the weekend just to ensure that we’ll all be good and stressed for Monday.

Obviously, one is left to wonder how this happened? After all, the government’s finances may be strained, but unlike, say Greece, we in the U.S. are not so poor that we’ve had to sell the printing press. Demand for Treasuries remains high, the Federal Reserve stands ready to serve as the quantitative easer of last resort, and in essence the United States cannot default unless it wants to. And, as was recounted in Frank Partnoy’s FIASCO, ratings agencies see their jobs as rating the risk of default, not any other risk such as inflation. He recounts the example of a structured note that Morgan Stanley created that had an embedded put on the peso, meaning that if the peso fell below a trigger level the note holders would effectively be paid back in pesos instead of dollars. And yet the collateral and the cash flows supporting the bonds were as solid as the Bank of Mexico, so this issue gained a AAA rating and retained it as the peso fell right through the trigger level and kept going.

Normally, I try to avoid getting political, but this downgrade is a reflection on politics, not economics and so I have no choice. A close reading of the Standard and Poor’s full announcement is in accord with these views. As I said, the U.S. cannot default unless it wants to, and it seems that the grounds for the downgrade is that the U.S. might want to — at least, it might want to more than it wants the two sides to set aside their partisan warfare. The first sentence of the rationale section reads “we believe that the prolonged controversy over raising the statutory debt ceiling and the related fiscal policy debate indicates that further near-term progress containing the growth in public spending, especially on entitlements, or on reaching an agreement on raising revenues is less likely than we previously assumed and will remain a contentious and fitful process.” It continues “the political brinksmanship of recent months highlights what we see as America’s governance and policymaking becomes less stable, less effective, and less predictable than what we previously believed. The statutory debt ceiling and the threat of default has become political bargaining chips in the debate over fiscal policy.” In other words, the default risk does not arise from our economy, but our politics. The deficits and the debt levels concern Standard and Poor’s, but they do so less than the political impasse that makes them impossible to address.

Although S & P labors to make clear that it “takes no position on the mix of spending and revenue measures…appropriate for putting the U.S.’s finances on a sustainable footing,” I suspect that this might be a run for political cover, as they will certainly need it come Monday. What I believe to be a major centerpiece of this ratings cut appears later in the report: “[O]ur revised base case scenario assumes that the 2001 and 2003 tax cuts, due to expire by the end of 2012, remain in place.” In other words, they contend that a certain contentious political faction whose name begins with an R will find some way of extending these tax cuts to hold hostage some necessary expenditure, just as they did in 2010 over extending unemployment benefits. And this is on top of the “calculation error” that the administration cited when challenging the S & P report.

Now, I have never been a fan of the Bush tax cuts. The ostensible purpose of them was to return a projected surplus to the American taxpayer. The sequel of events shows that such a move was unnecessary; two unfunded wars, a major expansion of Medicare, and a general failure to produce sustainable economic growth did an adequate job of mopping up the surplus. In fact, I think the only good thing about the Bush tax cuts was the expiration date. Even so, the debt ceiling crisis gave both parties the strength to do what had to be done to prevent a default. The deal that was reached enjoyed votes in favor from both sides in Congress. Likewise, I think the next time the Bush tax cuts fall due to expire there will be enough urgency left in the system to allow it to happen. After all, even with the deficit cutting measures and the bipartisan panel that went into the current debt ceiling deal (of course, I should point out that Congress is itself a bipartisan panel and normally it can’t agree on what day of the week it is), the deficit will still be big enough to cause concern. As such, I hope, and I think it is likely, that enough members of Congress will yield to economic reality to give the Bush tax cuts a dignified burial.

Even Grover Norquist, architect of the “no higher taxes” pledge that virtually all Republican representatives have signed, has said that the expiration of the Bush tax cuts will not violate the pledge. And if even the crusader of the anti-tax movement is willing to offer that concession, there must be something in it. And Nouriel Roubini described the U.S. situation as “manageable” because unlike most other advanced countries, we have plenty of room to raise taxes. Taxes as a percentage of GDP are much lower than in, say, most of the countries of Europe, and are also much lower than the historical average. And, as I have pointed out before, there is virtually zero correlation between tax levels and real economic growth, at least at the levels of taxation that have prevailed through recent U.S. history.

That said, this ratings downgrade is ultimately a small thing that looks like a big thing (unlike the debt ceiling deal, which was a big thing that looked like a big thing). The Federal Reserve has already come out with a notice that it will not affect risk capital decisions, and as long as Fitch and especially Moody’s do not pile on to avoid feeling left out, the impact of this decision should be muted apart from what I predict to be an interesting next week.

So, one is left to wonder why S & P did it. Perhaps they are of a political mind, hoping to get some resolution by pressing the issue. Perhaps they want to be the first ones who called the downgrade if the situation in Congress degenerates further. Perhaps they have no ulterior motives and are genuinely concerned about the current political situation.

The bigger question, though, is whether we should care. I doubt it is a good thing that our financial system has evolved to the point that one unelected, unappointed, unscreened analyst has the power to cause so much chaos despite the fact that he has done nothing more than dropping one letter. I think the better approach for market participants is to learn to ignore ratings agencies. If ratings agencies ever had a purpose, they abandoned it around when they decided to rate subprime securities that didn’t even have a full business cycle of data to work with, and now that they have downgraded a riskless debt that both parties are willing to set aside their deeply held beliefs in order to prevent the default of, Standard and Poor’s has hammered what should be the final nail into its eventual irrelevance.

A credit rating is not a magic talisman. As my readers well know, I have recommended several junk bonds on this website before, and at no time did I require a ratings agency’s stamp of CCC on it to let me know what I was taking on. I can do my own research, and a ratings agency’s opinion is always second — and a distant second — to my own opinion. And now that S & P have taken this action, I feel justified in this method. I still consider the debt of the U.S. Treasury safer than the debts of Automated Data Processing, Exxon, Johnson & Johnson, and Microsoft, because none of those four owns a printing press. And yet S & P would have us believe that the opposite is true, because those four companies are now rated higher than the Treasury. And yet everyone still knows, having seen last week, that no member of Congress will genuinely risk a default because secretly or openly they all know that a U.S. default will make Lehman Bros. look like a papercut.

So, I think it is time to move on from credit ratings. They are interesting, easy to understand, but they are ultimately not useful, and tend to retard analysis rather than encourage it. During the Goldman Sachs hearings in May of 2010, the senators made much of an email suggesting that Goldman Sachs, in peddling its subprime deals, should focus on “ratings-based buyers,” rather than the hedge funds that are sophisticated enough to know what’s going on. And anything that is attractive to a lack of financial sophistication is unattractive to me.

I fear, at least for next Monday, that my views on ratings agencies may not be taken up by the broader market. The two most important people in the United States are President Obama and Ben Bernanke, and not necessarily in that order. But if we continue to be thralls to the ratings agency system, the third most important person in the United States will be Raymond McDaniel. Who, you may well ask, is Raymond McDaniel? Why, he is the CEO of Moody’s, who can approve or veto a matching ratings cut.

So, this ratings downgrade may push the political system into taking some necessary deficit reduction action, and I hope it will put revenue raises back on the table. But in terms of actionable information, I find that it contains none at all. I only hope that market participants next week and thereafter agree with me.

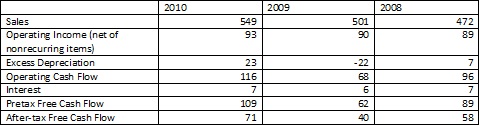

Black Box offers a free cash flow yield of 12.3%, which is attractive. Moreover, the cash flow yields have been robust, with earnings even in the 2009 period offering a free cash flow yield of nearly 10%. Black Box has also been acquiring smaller private competitors, having accomplished at least nine acquisitions in the last four years. As the acquisitions are of private companies I have no means of making an independent assessment of the acquisitions, but they seem to be at least paying for themselves.

Black Box offers a free cash flow yield of 12.3%, which is attractive. Moreover, the cash flow yields have been robust, with earnings even in the 2009 period offering a free cash flow yield of nearly 10%. Black Box has also been acquiring smaller private competitors, having accomplished at least nine acquisitions in the last four years. As the acquisitions are of private companies I have no means of making an independent assessment of the acquisitions, but they seem to be at least paying for themselves.