Acxiom (ACXM) – The Nerds of Marketing

Acxiom, a company that is very difficult to pronounce, is a large marketing consulting firm, with a specialty in data mining. The firm uses customer data gathered from clients, and its own proprietary database, to develop a multi-channel marketing strategy (e-mail, web advertising, mobile advertising, and direct mail, among others) for clients. Acxiom claims to have the largest single-owner consumer database in the United States, which it believes to cover almost all households in the United States, and the company also has a presence in Europe, China, Australia and New Zealand, and Brazil. In other words, these are the people who spy on your shopping preferences for targeted marketing campaigns.

In Acxiom’s latest 10-K, it claims that most of its client base is Fortune 1000 companies in the financial services, insurance, information services, direct marketing, media, retail, consumer, technology, automotive, health care, travel, and communications industries. The company normally works under contracts of at least two years, and claims to have a high retention rate, although what constitutes “high” is unstated.

In Acxiom’s latest 10-K, it claims that most of its client base is Fortune 1000 companies in the financial services, insurance, information services, direct marketing, media, retail, consumer, technology, automotive, health care, travel, and communications industries. The company normally works under contracts of at least two years, and claims to have a high retention rate, although what constitutes “high” is unstated.

Acxiom claims to be a market leader in the United States, and competes against other large companies as well as smaller firms that have a more limited range of services. The competitive landscape in Europe is similar. In Australia much of the competition is local, and in Brazil the company has no direct competitors, but it would seem that some local competitors are cropping up and other international firms may be encoraching as well. The company has been engaging in numerous mergers with some of its smaller competitors, and it admits in its own filings (which are in full view of the Department of Justice and America’s small army of antitrust lawyers) that it is concerned about several of its single-service competitors banding together to provide an array of services that might compete with Acxiom itself.

Turning to the figures, Acxiom has a significant amount of excess cash on the balance sheet. The company has $207 million in cash and equivalents, and a total of $391 million in tangible current assets. Current liabilities total $229 million, which leaves a difference of $162 million, which is the amount of excess cash. This, when applied to a market cap of $1.04 billion, leaves $880 million as the market value of the company’s productive assets.

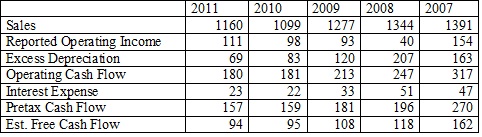

In terms of earnings, sales were $1160 million and reported operating income (net of a goodwill impairment) of $111 million. The excess of depreciation over capital expenditures (including capitalized software costs and data purchases) comes to $69 million, producing operating cash flow of $180 million. Interest expense comes to $23 million, which leaves pre-tax cash flows of $157 million. The company’s tax rates have been hovering around 40% for the last few years, and if we apply that, we have a free cash flow to equity of $94 million. This gives us a price/free cash flow ratio of 9.36.

I should point out that fiscal year 2009 and 2008’s earnings (Acxiom’s fiscal year ends in March) include restructuring charges of roughly $30 million and $40 million respectively. I should point out that the above calculation treats excess depreciation as taxable, while it is untaxable under the tax code. If it received the correct tax treatment, 2011’s earnings would have increased by $28 million. However, as we see, the amount of excess depreciation has been declining over time, and the present value of future excess depreciation may not be very large.

The source of the excess depreciation is Acxiom’s acquisitive nature; the company’s historical capital expenditures apart from acquisitions are inadequate. Normally, I assume that acquisitions neither add value, nor take it away (apart from investment banking fees). However, companies that use acquisitions to accomplish capital expenditures that they would ordinarily make outright can complicate this, by giving us a reason to treat mergers as capital expenditures. However, if Acxiom is engaging in mergers to contain the competition, they may find it unnecessary to replace the target company’s assets at the same rate that they depreciate. Furthermore, the goal in this valuation is trying to arrive at Acxiom’s sustainable earnings power, and although future acquisitions may be part of Acxiom’s business strategy, I cannot project the frequency and size of the company’s future deals. As such, the best I can do is present the data as I always have, with the above caveats.

So, we see from the above that, at least for the present year, Acxiom has stabilized after a series of earnings decline. Obviously, with discretionary income under pressure, the profit opportunities for a marketing company can similarly be limited, hence the overall decline in sales and profits. However, with the restructuring, profit margins seem to remain stable. Analysts are projecting a modest increase in sales and earnings in the coming couple of years (of course, that is what analysts do), and if the company has stabilized at this price, the company offers a robust yield on the market value of its capital assets.

However, the issue of Acxiom’s stabilization is not a given, considering the continued pressure on the consumer, even in Australia, China, and Brazil, which are generally considered to be showing stronger growth than in the US and Europe where the rest of Acxiom’s operations are. Accordingly, although this company is an enticing speculation, and would also be attractive if the price were to decline significantly. Even so, under the circumstances I cannot describe it as a pure value play.

Leave a Reply