Unsuitable for Managers who are not Warren Buffett (CCA Industries)

Damodaran on Valuation claims that unnecessary financial assets, such as stocks or bonds or other securities of other corporations, have no effect on a company’s valuation, since the risk-adjusted discounted cash flow they produce is equal to their present value, so there is no incremental benefit to owning them or decremental drawback from getting rid of them. Of course, this position assumes that markets are efficient which is at odds with both the central theory of value investing and presumably Damodaran’s own purposes in writing, since he did call his book Damodaran on Valuation, rather than Damodaran on Giving up and Becoming an Actuary.

However, he does raise a good point; why should the shareholder pay management fees and submit to double taxation for a firm to hold financial assets that the shareholder could just go out and buy if the company had just issued a dividend instead of paying for the assets? The only possible explanation is that the firm is in fact capable of producing better investment results than the majority of its shareholders. Damodaran cites Berkshire Hathaway as a rare example of this firm; most corporate managers who are not Warren Buffett realize that investing in securities to produce above-average returns is difficult to do well and indefensible if done badly. Just ask any failed investment bank.

However, he does raise a good point; why should the shareholder pay management fees and submit to double taxation for a firm to hold financial assets that the shareholder could just go out and buy if the company had just issued a dividend instead of paying for the assets? The only possible explanation is that the firm is in fact capable of producing better investment results than the majority of its shareholders. Damodaran cites Berkshire Hathaway as a rare example of this firm; most corporate managers who are not Warren Buffett realize that investing in securities to produce above-average returns is difficult to do well and indefensible if done badly. Just ask any failed investment bank.

So, what do we do with a firm that does not seem to be aware of this principle? Specifically, CCA Industries Inc. (CAW), a tiny firm that makes low-end toothpaste and beauty products, reports that of its approximately $33.5 million in assets, $14.5 million are short-term investments or marketable securities. Year to date income produced by these investments has been $212 thousand, resulting in an annualized return of a bit under 3% as of the May 31 reporting period. However, for their actual operations, the other $19 million in assets has produced pretax earnings of $1.29 million, which is a return on assets of 13.6% if it is doubled to fill out the year. (And this assumes that all the cash on their balance sheet is needed for their operations). So, it is pretty apparent that the financial assets they hold are superfluous. In fact, if they did distribute all of their excessive assets, the market cap, currently 29.5 million, would drop to 15 million, which would be amply supported by $1.7 million in after-tax earnings (apart from accounts payable they have virtually no debt to speak of).

This being the case, how has CCA gone this long without some enterprising investor raiding it? According to the writeup at the Value Investor’s Club, it is because the firm is controlled by two old men in their 70s. There was a deal proposed last year to take the firm private, but it fell through. Otherwise, the stock seems to be entirely under Wall Street’s radar.

If Damodaran is correct, and the unnecessary financial securities do not produce any actual value to the company, then buyers of this company are in fact buying $19 million in actual capital, $2.6 million in operating earnings, and $14.5 million of excessive holdings taunting them. Unfortunately, as long as the two old men control the company there is no realistic way to force the distribution of the excessive assets, and in the meantime the firm’s aggregate return on capital will be suboptimal, resulting in a depressed share price. We hope for the sake of the noncontrolling shareholders that the company’s owners will listen to reason.

P.S. They pay a 6.7% dividend, although the dividend history has been somewhat erratic.

Edit: The firm just announced earnings, but without the concrete detail that breaks down operating versus investing earnings. When I have those, I will do an update. I don’t expect too much to change in my analysis, though.

Update:Â Their interest and dividend income is up to 245 thousand year to date, producing a return on capital investments of 2.3% on an annualized basis (although they also have some capital gains which pushes the total to 2.8%). Their return on assets from their actual operations is 14.0% pretax. QED.

Fairpoint recently acquired Verizon’s land lines in New England for $2.3 billion, which it turns out was a few hundred million too much, thus demonstrating the value investing principle that there are no good or bad investments, only good or bad prices. After all, anything can be at least liquidated, and with a bankruptcy in the works that is looking like a distinct possibility. Since that time, declining revenues have sunk their income, causing them to suspend their dividends in 2008 and now, it seems, to suspend their interest payments as well.

Fairpoint recently acquired Verizon’s land lines in New England for $2.3 billion, which it turns out was a few hundred million too much, thus demonstrating the value investing principle that there are no good or bad investments, only good or bad prices. After all, anything can be at least liquidated, and with a bankruptcy in the works that is looking like a distinct possibility. Since that time, declining revenues have sunk their income, causing them to suspend their dividends in 2008 and now, it seems, to suspend their interest payments as well. Obviously, it is too early to say anything, and the rumor of Windstream even buying the debt has not been confirmed, but since Windstream has embarked on two opportunistic acquisitions already in the last year, it would be a positive development for them to be feasting on Fairpoint’s corpse alongside the other vultures. As for ourselves, we like low-hanging fruit and have no objection if some fruit gets blown off the branch by a strong economic headwind. So, if the rumor is true this is another positive for Windstream, although they might want to recall that acquiring more than they can chew is what killed Fairpoint to begin with.

Obviously, it is too early to say anything, and the rumor of Windstream even buying the debt has not been confirmed, but since Windstream has embarked on two opportunistic acquisitions already in the last year, it would be a positive development for them to be feasting on Fairpoint’s corpse alongside the other vultures. As for ourselves, we like low-hanging fruit and have no objection if some fruit gets blown off the branch by a strong economic headwind. So, if the rumor is true this is another positive for Windstream, although they might want to recall that acquiring more than they can chew is what killed Fairpoint to begin with. Some of you may recognize our old friend the yield hog from the

Some of you may recognize our old friend the yield hog from the  As to borrowing the money from healthy banks, any effect on the private sector from removing the money would be dwarfed by the fallout from the massive bank run if an investor actually suffered a loss due to the bankruptcy of the FDIC. Of course, since the bankruptcy of the FDIC fund is not seriously an option this is not going to occur. However, it seems to be unreasonable for the FDIC to have to pay interest to one bank on behalf of the depositors of another. Using the Treasury’s line of credit would make more sense, although it does look like another bailout to the banking industry, and banks themselves are not looking forward to higher fees down the road to repay interest and principal.

As to borrowing the money from healthy banks, any effect on the private sector from removing the money would be dwarfed by the fallout from the massive bank run if an investor actually suffered a loss due to the bankruptcy of the FDIC. Of course, since the bankruptcy of the FDIC fund is not seriously an option this is not going to occur. However, it seems to be unreasonable for the FDIC to have to pay interest to one bank on behalf of the depositors of another. Using the Treasury’s line of credit would make more sense, although it does look like another bailout to the banking industry, and banks themselves are not looking forward to higher fees down the road to repay interest and principal. Calumet Specialty Products (CLMT) is an investment partnership that produces various petroleum products. It currently pays a dividend of 12.3%, and has a P/E ratio of 10.68, so it is almost covered. However, their earnings seem to have been fairly variable over the years and sales have been dropping from their heights, so this is probably not a good source of sustainable cash flow, although their dividends have been covered by operating cash flow, if not net earnings, for three of the last four quarters.

Calumet Specialty Products (CLMT) is an investment partnership that produces various petroleum products. It currently pays a dividend of 12.3%, and has a P/E ratio of 10.68, so it is almost covered. However, their earnings seem to have been fairly variable over the years and sales have been dropping from their heights, so this is probably not a good source of sustainable cash flow, although their dividends have been covered by operating cash flow, if not net earnings, for three of the last four quarters. Much of this fiddling with nonrecurrent events is the fault of accounting rules anyway. When it comes to goodwill, writeoffs take on an unusual character. Goodwill represents the purchase price paid to acquire a company that is in excess of the assets of that company. It represents the excess returns available from buying an established company instead of just replicating it, or, if you believe Damodaran, some of it comes from the “growth assets†of a company – the assets it will one day acquire to produce its growth and future excess returns. A lot of analysts advocate ignoring goodwill entirely, when it first shows up as an asset and when it is inevitably written down when conditions deteriorate. After all, if there are excess returns in a business they will show up in the income statement anyway, so counting both the excess returns and the goodwill looks like double counting. Goodwill nowadays, instead of being linearly written down over time, is now written down whenever, in the opinion of accountants, the excess returns it generated are no longer there. Since this essentially trades one accounting fiction for another, I can’t say that it’s solved the problem of dealing with intangibles, but it does make the data more frequently subject to large, discrete abnormalities.

Much of this fiddling with nonrecurrent events is the fault of accounting rules anyway. When it comes to goodwill, writeoffs take on an unusual character. Goodwill represents the purchase price paid to acquire a company that is in excess of the assets of that company. It represents the excess returns available from buying an established company instead of just replicating it, or, if you believe Damodaran, some of it comes from the “growth assets†of a company – the assets it will one day acquire to produce its growth and future excess returns. A lot of analysts advocate ignoring goodwill entirely, when it first shows up as an asset and when it is inevitably written down when conditions deteriorate. After all, if there are excess returns in a business they will show up in the income statement anyway, so counting both the excess returns and the goodwill looks like double counting. Goodwill nowadays, instead of being linearly written down over time, is now written down whenever, in the opinion of accountants, the excess returns it generated are no longer there. Since this essentially trades one accounting fiction for another, I can’t say that it’s solved the problem of dealing with intangibles, but it does make the data more frequently subject to large, discrete abnormalities. LINE is an oil and gas producer, and the bizarre PE ratio comes from the fact that, like many producers, they use derivatives to hedge their exposure to the price of oil and natural gas. However, accounting rules require them to record the changes in value of their derivatives during each earnings period, but they are not permitted to record the counterbalancing change in the oil and gas they hold. Since LINE holds three to five years’ worth of production of these derivatives, any hiccup in the price of oil or natural gas will affect those derivatives by several times what their current results will be affected by. So, ironically, the derivatives that are supposed to make their operations more stable make their reported earnings quite unstable.

LINE is an oil and gas producer, and the bizarre PE ratio comes from the fact that, like many producers, they use derivatives to hedge their exposure to the price of oil and natural gas. However, accounting rules require them to record the changes in value of their derivatives during each earnings period, but they are not permitted to record the counterbalancing change in the oil and gas they hold. Since LINE holds three to five years’ worth of production of these derivatives, any hiccup in the price of oil or natural gas will affect those derivatives by several times what their current results will be affected by. So, ironically, the derivatives that are supposed to make their operations more stable make their reported earnings quite unstable. It is, in fact, the New York Times Bestseller List. In a classic investment comedy book, Rothchild’s

It is, in fact, the New York Times Bestseller List. In a classic investment comedy book, Rothchild’s  As an aside, China has pegged its currency to the United States dollar for a number of years, in order to perpetuate the trade deficit and build up a substantial pile of Treasury holdings. We ran the price of oil up to $140 a barrel just to shake them off, and now they have the flaming nerve to

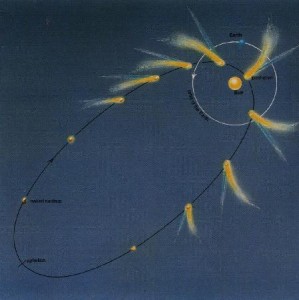

As an aside, China has pegged its currency to the United States dollar for a number of years, in order to perpetuate the trade deficit and build up a substantial pile of Treasury holdings. We ran the price of oil up to $140 a barrel just to shake them off, and now they have the flaming nerve to  Obviously, when the market is in a depressed mood bargains are more likely to be available, but the central tenet of value investing is that a security’s price and value behave like a comet orbiting a star; they’re locked together as if by gravity but only on rare occasions are they close. However, it is the nature of all financial assets that they turn into cash sooner or later; for bonds, it’s not only sooner but according to schedule, for stocks, often but not always later because they are constantly selling, buying, and shuffling around assets.

Obviously, when the market is in a depressed mood bargains are more likely to be available, but the central tenet of value investing is that a security’s price and value behave like a comet orbiting a star; they’re locked together as if by gravity but only on rare occasions are they close. However, it is the nature of all financial assets that they turn into cash sooner or later; for bonds, it’s not only sooner but according to schedule, for stocks, often but not always later because they are constantly selling, buying, and shuffling around assets.