Real Mex bonds: High yield and robust

UPDATE: On the night of July 20, 2011 the company informed the major ratings agencies that it did in fact miss the latest interest payment on the bonds. As I stated below, the cash flows to the company are sufficient to support the ultimate value of the bonds, but now that value is likely to be realized after a bankruptcy process. I did predict that default/restructuring/bankruptcy was more or less inevitable for these bonds, but I am surprised that it happened so soon. Obviously, that bit about the possible “sweetener” of some extra coupons in the article below no longer applies.

As my readers may recall, I have been interested in high yield debt as well as equity. However, opportunities in this area have been somewhat lacking in the current market as compared to, say, April of 2009, and I have been finding enough equity opportunities to keep me busy. Nonetheless, I find high yield opportunities to be quite enjoyable and suited to my investing style, and I would hate to abandon my favorite asset class.

One interesting opportunity I have found is the bonds of Real Mex, a private company that operates a flock of casual Mexican dining restaurants mainly in California. The company owns a total of 181 restaurants, most of which consist of the three restaurant chains of El Torito, Chevy’s, and Acapulco, which are the largest chains of Mexican full service casual dining in California. The company’s free cash flow to the firm has been declining, but for now the interest of the bonds in question is covered. However, it is likely that Real Mex would benefit from a bankruptcy or financial restructuring, and these bonds would be expected to hold their value in either event. Robustness to bankruptcy is essential to a high yield investor, and indeed to any bond investor, if they would admit it.

One interesting opportunity I have found is the bonds of Real Mex, a private company that operates a flock of casual Mexican dining restaurants mainly in California. The company owns a total of 181 restaurants, most of which consist of the three restaurant chains of El Torito, Chevy’s, and Acapulco, which are the largest chains of Mexican full service casual dining in California. The company’s free cash flow to the firm has been declining, but for now the interest of the bonds in question is covered. However, it is likely that Real Mex would benefit from a bankruptcy or financial restructuring, and these bonds would be expected to hold their value in either event. Robustness to bankruptcy is essential to a high yield investor, and indeed to any bond investor, if they would admit it.

The bonds in question are $130 million in senior secured bonds due January 1, 2013. The bonds have the distinctly unsubtle coupon of 14%–normally one might expect a high yield to come from a significant discount to par, but in this case the bonds themselves have the high yield on their face. Actually, at present the bonds also do trade at a discount, and based on the current price level of 92.50 the yield to maturity is 20.2%. Real Mex is required to use any money that the bond indenture defines as “excess cash flow” to offer to repurchase these bonds, but there was no such cash flow available in 2010.

These bonds rank behind a revolving credit facility and letter of credit agreement; the credit facility has a maximum availability of $15 million and as of the latest quarterly filing there was $4.6 million drawn on it. The letter of credit facility is apparently unused, has a maximum draw of $25 million, and has $8.4 million available on it as of the latest quarterly filing. This credit facility falls due in July of 2012, and bears a variable rate plus a fixed margin, which as of the latest filing totaled 9.25%.

Real Mex’s other major debt consists of an unsecured debt owed, at least in part, to the company’s owners. This debt bears an interest rate of 16.5%, but it is payable partly in kind. As this debt is unsecured, it ranks lower in priority than these bonds.

The large interest payments are presently covered by free cash flow to the firm, as I shall calculate below. Sales and free cash flows are declining, but the rate of decline appears to be slowing. However, the large interest requirements are consuming the bulk of the company’s free cash flow, making it difficult for the company to chip away at its debt burden. As such, I am skeptical of the company’s ability to refinance this bond issue, or perhaps even the credit facility if there is a large balance on it when it falls due. However, the existence and persistence of positive free cash flow on the company level would suggest the viability of a bankruptcy or other restructuring.

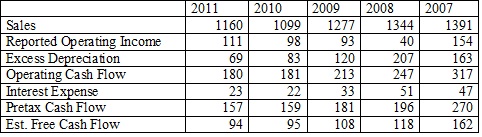

Turning to the figures, in 2010 sales were $478 million, reported operating income net of impairments was $6.5 million, plus excess depreciation of $18.3 million produces a total of $24.9 million in free cash flows to the firm. Interest accrued that year was $28.8 million, but $4.6 million of that was paid in kind, and interest actually paid that year, according to the statement of cash flows, was $19.4 million.

In 2009, sales were $501 million, operating earnings net of special items were $0.7 million, and excess depreciation, neglecting a massive debt discount amortization, was $27.1 million, producing a total of $27.8 million. Interest expense that year was stated at $46 million, but $25 million of that amount was the debt amortization referred to above, and $1 million was paid in kind. Actual interest paid that year was $15.7 million according to the statement of cash flows.

In 2008 sales were $550 million, operating earnings net of impairments were $9.7 million and there was excess depreciation and amortization of $4.4 million, producing free cash flow to the firm of $14 million million. Interest accrued during that period was $20.5 million, but actual interest paid according to the statement of cash flows was $17.8 million. The first quarter of 2011 is indicating further diminution in earnings, with sales of $116 million as compared to $120 million for the same quarter last period, and $5.6 million in free cash flows to firm rather than $7.9 million in the same quarter last year.

So, the interest on the bonds in question is $18.2 million per year, and on the credit facility, if fully drawn, there would be an additional $1.4 million, plus whatever might be drawn on the letters of credit, although there may be some restrictions on drawing the full amount. At any rate, the current level of cash flows covers the potential interest requirements by approximately once, which is hardly a margin of safety, and which brings into question the possibility of refinancing no matter what interest rate is offered.

However, if we assume that, say, $20 million is a reasonable estimate of the firm’s free cash flow in future, we can assess the value of a restructured firm. The beauty about contemplating a Chapter 11 is that we are permitted to play with the capital structure to render it more reasonable. Allowing for an interest coverage ratio of a more reasonable 3x, that would allow Real Mex to allocate $6.66 million to interest. At a more reasonable interest rate of 9%, this would allow for a bond issue of $74 million. The remaining free cash flow, after, say, 40% in taxes, would leave $8 million in free cash flow to equity, which, if capitalized at 10x, produces an equity value of $80 million. Thus, it would be reasonable to assume that the entire value of the firm would be $154 million. This compares favorably with the current value of the bonds, $120 million, plus the maximum of $15 million in borrowings on the line of credit (letters of credit are used to finance large purchases and not for general business purposes, so I assume they are unlikely to be significant).

As a result, the holders of the bonds may receive some more coupons, which would be an attractive sweetener, with a current coupon of 15.1%, as I do not believe the main crisis for the company will arise until the bonds come due for refinancing. Even so, the main feature of these bonds is that in the event of bankruptcy or a similar workout, the existing bondholders are likely to accede to the ownership of the bulk of the securities the reorganized company, whether in the form of debt or equity. And as I have calculated, the value of the reorganized company stands a good chance of ending up being greater than the current price of the bonds. Of course, that is at the endpoint of a bankruptcy that may be protracted, but it is nonetheless an exciting opportunity that serves to increase the safety of these bonds beyond what the 20% yield would imply. Even so, there may be a long period of market chaos, low prices, and illiquidity to ride out, although a prepackaged bankruptcy, which takes only a few months, is also a possibility. I should also note that Real Mex’s current owners acquired it as the result of a previous equity-for-debt swap in November of 2008, although since the financial world was coming to an end around then, this occurrence should not be surprising.

These bonds offer a 20% yield in the event that they are refinanced and ultimately paid off, and have as their source of safety the fact that even in bankruptcy the bonds will ultimately retain their value. Accordingly, enterprising fixed income investors who are not afraid to stare down a Chapter 11 will find these bonds an attractive candidate. And, of course, any further reduction in price in the near future will make them more attractive.