Place your bets on the Mohegan Tribal Gaming Authority

As I seem to be in a mood to find junk bonds lately, I am pleased to present you with the bonds of the Mohegan Tribal Gaming Authority. The Mohegan Tribe operates a massive casino in Connecticut, one of only two casinos in New England, as well as several other ventures.

The company has been attempting to open casinos on other Indian reservations in the recent few years, but owing to certain regulatory difficulties, both proposed casinos have been put on hold. Coupled with the drop in revenues from the economic slowdown, which seem to be leveling out, the ability of the Mohegan Authority to service its debts has come into question. Although their operating incomes have never actually failed to cover their interest requirements of roughly $100 million per year, they certainly have come close, as I shall state below.

The Mohegan Authority’s financial statements require two species of adjustment. The first is the one I customarily make, which is adding back depreciation and removing capital expenditures in order to reach a convenient proxy for free cash flow to the firm. In Mohegan’s case, though, the numerous projects they embarked on, including the drive to open two other casinos, a major expansion to their existing casino (now on hold), and the purchase of a WNBA franchise, has served to give their capital investments a remarkably uneven quality from year to year. As a result, I can find no better course than to average out their capital expenditures for a considerable number of years, which comes to about $70 million in capital spending per year. It may be that given the apparent regulatory opposition to expanding casino gambling as well as the economic slowdown, the company may be in a position to ratchet down their future capital expenditures. This would increase free cash flow, but with so many projects on hold indefinitely, we may expect to see (noncash) writeoffs in future as well, which may drag on the price of the bonds.

The financial statements also require another adjustment, and this one is company-specific. The Mohegan Authority made a deal with a developer in 1998 that requires them to hand over 5% of their revenues until 2014. The company records their projected payments under this deal as a liability. In my view, this figure should not be treated as a liability, since the only way for the liability to accrue is for the company to do business and so it should simply be treated as an operating expense. In fact, the current treatment leads to the paradoxical effect that the company’s liability goes up the better the company does. Accordingly, when calculating operating income to arrive at interest coverage, the projected change in this liability, which is separate from amounts actually paid under the agreement, should also be stripped out.

So, adding back in the change in the liability (which can be negative, as it was in 2008 and 2009), adding back in depreciation, and removing $70 million from operating income to account for capital expenditures (or a prorated amount for the 3 quarters of fiscal year 2010), we get the following figures for available operating income:

2004: 180

2005: 192

2006: 208

2007: 232

2008: 123

2009: 126

2010 ytd: 159

I would like to focus on the last three years, because two of them were very low years, and the current year may give us some insight into where the company stands now. The Mohegan Authority has several classes of long-term debt, including $527 million in bank loans, $193 million in privately placed 11.5% senior notes, $250 million of 6.125% senior notes due 2013, and a family of subordinated notes with $475 million outstanding. Adding back in payables and miscellaneous liabilities and removing the liability for their deal with the developer, the Mohegan authority has total debt of approximately $1.9 billion, set against $2.27 billion in assets, most of them long-term and/or intangible.

In terms of interest coverage, the total interest paid year to date, apart from amortizations and other noncash items, comes to $82 million so far this year. This represents an interest coverage ratio of nearly 2x, and typically the summer is prime gambling season at the Mohegan Authority, so the full year results may show even more improvement. However, in 2008 and 2009, interest paid was $96 million and $102.4 million, resulting in interest coverage ratios of 1.28x and 1.24x. However, the senior bond, has a coverage ratio of 3.5x in even the worst years when one strips out the interest of all bonds subordinate to itself.

So the question becomes which class of debt to buy; the 6.125% senior notes or one of the subordinated notes. Both classes of debt are rated CCC+, which seems to be a favorite rating around here; Bon-Ton’s bonds and WNR’s convertible bonds are also CCC+, and it may be that the ratings agencies reserve this rating for bonds that could conceivably justify a rating in the B’s, but don’t want to go out on a limb by actually giving them one. Especially now that the subprime debacle has naturally made them worried about handing out ratings that are too high.

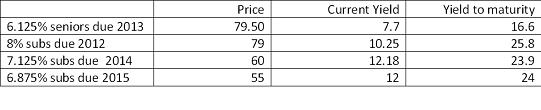

The 6.125% senior notes due 2013 currently trade at a 79.50, has a current yield of 7.7% and a yield to maturity of 16.6%, which would be a respectable return for anyone. Among the three issues of subordinate debt, the 8% notes due 2012 trade at 79, currently yield 10.25% and offer a yield to maturity of 25.8%; the 7.125% notes due 2014 trade at 60, currently yield 12.18% and offer a yield to maturity of 23.9%, and the 6.875% notes due 2015 trade at about 55, offer a current yield of 12 and a yield to maturity of 24% (my bond screener says that there is a bid/ask spread of 8 on these bonds, so I’m just averaging the two).

I am of two minds when it comes to the relative safety of the senior versus subordinate bonds. Benjamin Graham, in his excellent Security Analysis , advocated satisfying oneself that all of the bonds of a company are safe and then buying the highest yielding one, but that was his advice for generally investment-grade debt. On the other hand, as stated in Stephen Moyer’s vitally useful guide to distressed and bankruptcy investing, Distressed Debt Analysis

, seniority really comes into play in a bankruptcy. However, I am not sure how a bankruptcy would affect an Indian casino, because under the law only a tribe may own an interest in an Indian casino, so the usual outcome of a class of bondholders becoming the new stockholders is unavailable. Even so, any workout would result in the senior debtholders taking much less of a haircut.

That said, with the lower capital requirements from stalled expansion projects, I don’t think that bankruptcy is anywhere near imminent, although the Mohegan Authority does seem to have to roll over their debts at higher yields. So the 8% subordinate bond due April 2012 would seem attractive at first glance, with a yield of 25% and a short time horizon (only 19 months). But if you find yourself asking “What could possibly happen in 19 months?”, ask yourself what happened in the 19 months starting in April of 2007. Given the currently tenuous situation, I do think the more defensive approach of the 6.125% senior notes, with their current yield of 7.7% and a yield to maturity of 16.6%, offer an excellent return. One can always move down the seniority ladder when and if the situation at the Mohegan Tribal Gaming Authority improves.

PS: I am aware that certain followers of socially responsible investing would prefer not to receive income from activities such as gambling. I take the position that since investments purchased in the secondary market do not result in any cash actually going to the company in question, then receiving the income from the bonds does not equate to supporting gambling. In fact, there would be a certain poetic irony if, say, Gamblers Anonymous invested its spare cash in the securities of casino operators so it could direct the casinos’ own profits against them (or from a more cynical standpoint, it’s hedging its bets). Or, if I may coin the expression, It is not what goeth into a man’s pockets that defiles him, but what cometh out of a man’s pockets that defiles him.