Inflation: Does Say’s Law even Apply?

I was watching the latest hearing of Jerome Powell before the Senate Banking committee (as one does), and as expected the Democrats were congratulating themselves on unemployment being so low and workers finally having enough bargaining power in the labor market to acquire higher real incomes for the first time in forever. And then both parties added “And this is causing a notable uptick in inflation rates, so we’re hoping you can put an end to these developments as soon as possible.”

Naturally this led to thoughts about the aggregate supply and demand, and whether it is actually possible to get growth without increased prices and whether supply or demand is in the driver’s seat. And naturally my thoughts turned to Say’s law, beloved of supply-siders, which holds that supply creates demand. There is a certain logic here, since one cannot demand a good that is not supplied, although it is equally valid to say that one can be perfectly ready to supply a good, it will not be supplied until it is demanded.

But, consider an ordinary transaction whereby person A buys $1000 in goods and services from person B. Then B can buy $1000 in goods and services from C, and so on in that fashion throughout the entire world, so that one person’s decision to buy $1000 in goods, or $1 in goods, or 1 penny in goods, will echo around the world and produce an infinite GDP. And yet, GDP is obviously not infinite. Why?

Obviously, part of it is that it takes time to figure out what to demand and whom to demand it from, but that isn’t an issue in the time-compressed world of basic economic models (aside: economic models would be more acceptable if they all ended with the word “eventually”). But to Say, I suppose, the more fundamental reason is that the economy’s ability to supply goods beyond what is demanded is physically limited, and so GDP cannot rise beyond the economy’s ability to supply it.

The bigger problem, of course, is the invention of money. Keynes himself criticized Say’s Law as only valid in a barter economy, because with money it is feasible to supply a customer well in advance of demanding anything from him or anyone else. And since the marginal propensity to consume declines with income, obviously some of the money will be diverted to savings, so there’s a perfectly sensible reason why demand will eventually burn itself out.

So, as we all know from Econ 101, the supply curve is positively sloped and the demand curve negatively. However, those constructions do not rule out the possibility that the curves are horizontal or vertical. I do not believe that the aggregate demand curve is horizontal, at least until we have invented the Star Trek replicator, but it is conceivable that the demand curve is vertical at least in the short term, because, per Keynes, demand for consumer goods is a function of income, and demand for capital goods is a function of a lot of things, including the expected course of future income and opportunity costs, and setting aside “animal spirits,” those things do not change unless future developments change them. At any rate, it can be treated that way.

And what is the shape of the aggregate supply curve? Presumably it is not always horizontal; if it were possible to have any level of supply at a given price then we would just as soon have a high supply as a low one and the senators from the banking committee above would not be concerned with inflation. But the question remains, is it vertical?

However, one wonders if we are having Say say more than Say said. It is one thing to say that quantity supplied equals quantity demanded; it is quite another to say that supply = demand. The first statement is true by definition; the second one depends on assumptions that must be examined. Also, I was talking earlier about the relationship between GDP and price level, and if the supply curve is identical to the demand curve, price entirely falls out of the equation.

I would say that this is not the case, or at least not all the time. One of the implications of Say’s law is that ultimately supply cannot exceed demand since supply is what creates demand, but as is said, severe recessions and specifically the Great Depression would seem to refute this view, and if your economic model cannot predict something that has already happened, some revision is in order.

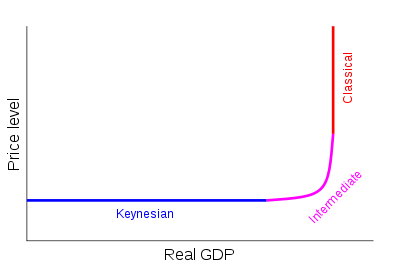

Fortunately, we have wikipedia to come to the rescue. In their view the supply curve is divided into three sections. In the Keynesian section, where severe recessions live, the supply curve is nearly horizontal, and any additional consumption is just drawing up slack in the market. We have seen this in our most recent financial crisis, wherby unemployment was halved, GDP increased for ten years straight, and somehow inflation actually came in below expectations. It would be tempting to think of the Keynesian section as a free lunch, but remember, the concept of the Keynesian section is drawing up the slack in the economy, and the slack had to have been created before the recession it. In other words, the lunch was already paid for but no one wants to eat it.

In the intermediate section, higher GDP does come at the cost of higher prices. I would suggest that this is the “normal” state of the economy, where there is a tradeoff between GDP growth and inflation and where we are living most of the time and the Federal Reserve tries to keep us.

But what is that vertical bar over there on the right side of the graph? It’s the “classical” section, where the supply curve is in fact vertical: the economy is firing on all cylinders and there is no slack to draw up. So, as discussed above, the GDP is in fact independent of the price level; Keynesian stimulus in this situation could increase inflation potentially infinitely without affecting the real GDP. I would argue that this is what was going on in the 70s’ stagflation.So, despite the temptation to throw Say’s Law onto the heap of failed ideas, it is clear that under some theoretical and even real-world circumstances where it would apply, and having made those circumstances clear we are in a better position to use it as a guide to policy.

Leave a Reply