In a Volatile Market, Step Back and Read

The market has been going through some troubling times lately, and the financial sites are full of doomsday articles (although after a few quiet trading days in January, people seem to be in a much better mood). I can readily understand the desire to avoid making bold long moves in the market, as we may be in the last gasps of a bull market (just as we were last year, and the year before that).

Personally, I have not been inordinately worried about the historically high valuations because of the unusually low level of long term interest rates. Most financial articles I’ve read take pains to point out that bond prices and yields go in the opposite direction, but they never bother to point out that stocks and yields work the same way. At least in terms of basic financial theory, stocks are priced the same way as bonds in that expected future cash flows are discounted to present value, and to the extent that recent market movements are the result of expected long-term interest rate increases caused by normalization of Federal Reserve policy, a drop in valuations is only to be expected. My thinking is that we have less of a bubble and more of a balloon that can have the air let out of it without popping.

But, if people aren’t buying aggressively, they certainly need something to fill in their free time, and that makes me think about books. And not just the quality investing/finance/economics books (though I have recommendations in that vein), but in general.

A lifetime ago, when I was in college, it was natural for students to sell their textbooks back at the end of the quarter, and inevitably some books could not be sold back, possibly because a new edition came out, or because of the book’s condition, or (ideally) the course it was for was simply not being offered next quarter and the bookstore had no use for it. There was a large table next to the buyback window where the disappointed students could just dump their unsold books for anyone who was interested. And I, being an enterprising lad, would just scoop up those books by the armload to sell them online. They say that value investors are born, not made, and it seems to me that profiting off of other people’s cast-off books is not so different from profiting off their cast-off stocks. At any rate, having my rent paid was worth having every wall of my apartment taken over by bookcases.

I don’t know that such a method would work nowadays. Textbook publishers use every trick in the book to come up with either frequent new editions or course-customized editions that cannot be resold; campus bookstores are getting better at finding a home for unwanted books anyway, and finally the used books at amazon.com are dominated by high-volume resellers such as Thriftbooks, Half Price Books, the various Goodwills, etc., who have a script to go through and undercut each other by a few pennies. And in the section where the condition of the book is supposed to go, they just copy-paste boilerplate descriptions or just a blurb about their own company; you often have to scroll through several pages of used offerings to find a single offer that looks like the seller actually had the book in their hands when they wrote it.

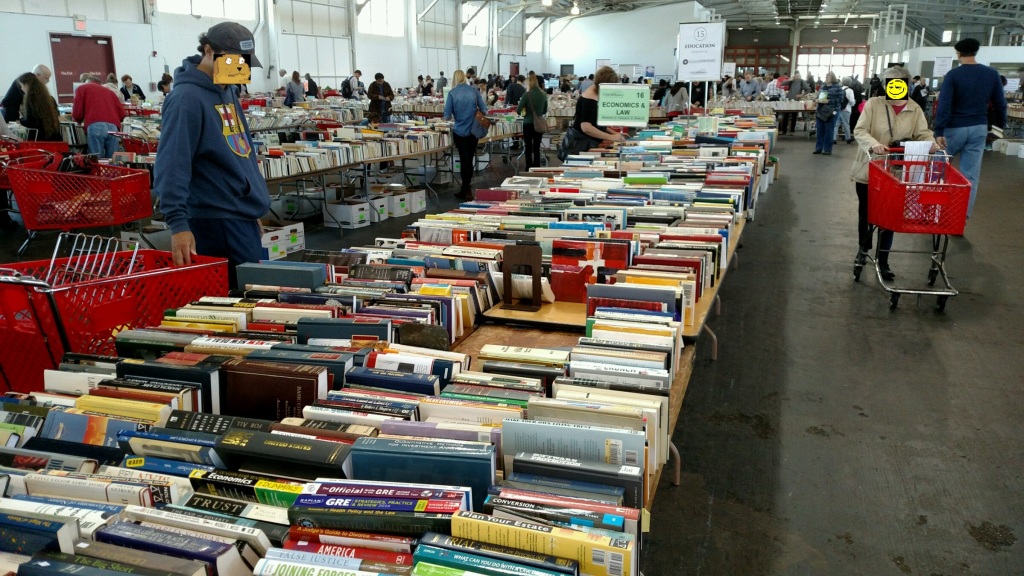

Even so, I still accumulate books, for use if not for resale. And my favorite source is library sales, where libraries sell off partly their discards, but mostly the donations they receive, typically at very reasonable prices. As Charlie Munger says, he has never known anyone who is successful in a field requiring broad knowledge who does not read pretty much all the time (an object lesson for more than a few politicians), and in terms of dollars per hour, used books are pretty much at the top of the list of ways to pass the time.

However, at the library sales also see a curious phenomenon of people going through with barcode scanners, feeding the UPCs of books to a mobile app which looks up the prices of books on amazon.com or other sites, in order to buy and resell them. This activity makes no sense to me for various reasons. Even setting aside the current state of used book sales, most libraries sort through their donations for books that are worth selling online anyway, and either sell the valuable books themselves or set their sale prices accordingly. Furthermore, these online lookup tools are ubiquitous enough that any book being scanned at a library sale has no doubt been scanned and rescanned by other sellers, and been rejected by them. In other words, the only way for a seller to find a worthwhile book with these scanning tools would be to have lower standards, in terms of profit margin, than any other book scanner in the place, and I would think that low standards are a poor way to justify the time, effort, and storage space required of keeping an inventory of used books.

And then I think back to investing. Isn’t it true that buying a financial instrument is also a battle of who-has-the-lowest-standards, since any stock or bond has been examined by hundreds or thousands of market participants who has declined to pay a higher price? On the whole, though, I think not. The reason that scanning books at book sales is so unattractive is that there are only a few variables involved: the book’s sales rank at amazon and its lowest selling price. But with securities, there is not only the buying and future selling price, but also the cash flows generated by the security in the meantime, which of course influence the buying and selling prices, but it must be conceded that the market is quite capable of being far off the mark in either of them. And it is this characteristic (plus portfolio management issues such as beta, correlation, etc.), that makes the two distinct. It is the same old distinction between an investor, who studies a situation to find a reasonable return on investment with safety of principle, and a speculator who simply hopes that they can find someone who will pay more tomorrow than what they paid today.

Leave a Reply