Make Yourself Immune to Interest Rates

I am one of the no doubt very few people in the world who enjoy watching the Federal Reserve Chair testifying before Congress. Among the issues presented in the latest round from Chair Yellen was the difficulty of old people coping with the low interest rate environment in living off their investment income. The Chair, while acknowledging these concerns, could naturally offer no comprehensive solution, partly because her mandates cover unemployment and price stability, not increasing the supply of old-people-appropriate investments, and partly because it’s not her job to offer portfolio management advice anyway.

The source of this criticism frequently seems to be the conservative side of Congress, which has often been suspicious by nature of the Federal Reserve and which has been stymied in its efforts to undermine the institution’s policies by the U.S. economy’s stubborn refusal to collapse into hyperinflation. Having lost, for the moment at least, the argument that the Fed is incapable of managing both inflation and unemployment, thus justifying the removal of one of these mandates, the conservative argument seems to be making up a new mandate, high yields on safe investments, apparently acting on the theory that if the Fed cannot handle two mandates it certainly needs three of them.

The source of this criticism frequently seems to be the conservative side of Congress, which has often been suspicious by nature of the Federal Reserve and which has been stymied in its efforts to undermine the institution’s policies by the U.S. economy’s stubborn refusal to collapse into hyperinflation. Having lost, for the moment at least, the argument that the Fed is incapable of managing both inflation and unemployment, thus justifying the removal of one of these mandates, the conservative argument seems to be making up a new mandate, high yields on safe investments, apparently acting on the theory that if the Fed cannot handle two mandates it certainly needs three of them.

Politics aside, though, it does seem unsatisfactory that old savers, or at least their desire to live off of interest income, should be collateral damage of the Fed’s policies, and the solution of taking on more risk is unpalatable even if the portfolio size and life expectancies of some retirees could justify it. And although value investing is effective for bonds as well as stocks–much of Ben Graham’s Security Analysis deals with bonds and many famous value investors have made a reputation and a fortune in fixed income–there is no readily apparent solution to low interest rates, particularly if the broader market is also reaching for yield, based on observed low and declining spreads between Treasury and high yield bonds. Not much can be done about low interest rates now.

But there is something that could have been done before now. As we all know, bond prices and yields move in opposite directions, a principle so well-known to fixed income investors that I don’t even need to cite it (oh, all right, The Handbook of Fixed Income Securities, Eighth Edition). Furthermore, we have ways of modeling exactly how far prices will move in response to a given change in yields, so that with the right choice of bonds we can insulate our future income against the actions of the Fed, or even in a pre-quantitative-easing world, of people other than the Fed as well.

The method is as follows. The value a bondholder derives from a bond comes from three factors. These are the market price, the interest the bond pays, and the proceeds of reinvesting the interest payments. If interest rates increase, it stands to reason that the market price will decline but the reinvestment income will increase, thus offsetting the decline in the market price. Likewise, if interest rates decrease, the price of the bond will rise but the reinvestment income will fall. But the question that concerns us is when the change in the market price and the change in reinvestment income will cancel each other, thus leaving us in the same position we were if interest rates had not changed at all. This method is called bond immunization.

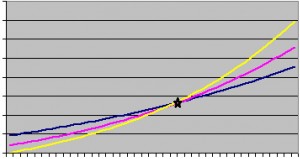

And it turns out that not only do those changes offset each other, but in theory they do so in quite an elegant manner. For a single bond, and for a single parallel shift in the yield curve (i.e. all relevant interest rates move by the same absolute amount), then the changes to market price and reinvestment income will exactly offset each other at a single point, regardless of which direction or how large the interest rate move is. That point is the duration of the bond. The duration, by the way, is the weighted average of a bond’s cash flows multiplied by the time until they are received, and also measures by what percentage a bond’s price will change in response to a change in interest rates. *

And it turns out that not only do those changes offset each other, but in theory they do so in quite an elegant manner. For a single bond, and for a single parallel shift in the yield curve (i.e. all relevant interest rates move by the same absolute amount), then the changes to market price and reinvestment income will exactly offset each other at a single point, regardless of which direction or how large the interest rate move is. That point is the duration of the bond. The duration, by the way, is the weighted average of a bond’s cash flows multiplied by the time until they are received, and also measures by what percentage a bond’s price will change in response to a change in interest rates. *

The point of this discovery is that if we are capable of predicting our future retirement expenses for a given year, we simply purchase bonds with a future value equal to those expenses and with the same duration as the year in question. This can be done for multiple years as long as durations are available, and at that point we arrive in the blurry and indistinct future that would be best met with equities. At any rate, the lower interest rates become, the longer bond durations become, so this method is even more usable in the current environment. This immunization technique is commonly used among those mythical creatures known as defined-benefit pension funds, and there is no reason the same logic does not apply to individual investors.

Well, when I say “no reason,” I am neglecting taxes. Also, interest rates have an irritating tendency to move in nonparallel shifts, which is to say that short-term and long-term interest rates sometimes shift by different amounts. But the biggest pain is that bond durations tend to drift over time, rather than decline perfectly in line with the approach of the year they were keyed to. The consequence of these factors is that a bond portfolio cannot be immunized and then ignored; it has to be rebalanced. However, all portfolios need to be rebalanced, so I don’t think this is a valid objection. The fact that there is a tradeoff between predictability of outcomes and not incurring transaction costs is known to anyone who has anything to do with hedging, see Nassim Taleb’s Dynamic Hedging: Managing Vanilla and Exotic Options.

It may be objected that this strategy is not strictly living off of one’s income, since half the time our bond prices will instantly go up and no matter what happens making these moves years in advance of the year in which we need the money means fiddling with our account balances anyway. But the goal in retirement investing shouldn’t be never to touch the principal; it should be to never outlive it. If we have more principal than otherwise through adopting this immunization strategy, and we have to draw it down in the target year, that is the strategy working as intended. And, really, if we never intend to touch our principal what is the point of having it?

In general terms, those who refuse on principle to invade their principal, and the conservative Congressmen at Chair Yellen’s hearing, are missing the point. They are analyzing assets in a vacuum, rather than taking into account the liabilities those assets are intended to meet. This is at best a suboptimal method and at worst one that leads to inadequate income, since interest rates are what they are and unless we happen to be Chair Yellen, we have no control over them but can only position ourselves in advance to respond to changes in them. And, since bond immunization works when interest rates rise as well as fall, the current concerns about the impact of the present tapering of quantitative easing suggests this strategy as much as the cutting interest rates and quantitative easing itself did.

It may further be objected that this strategy is complicated, requires a great deal of attention, and often requires a large portfolio to make the additional transaction costs worth the trouble. These objections are certainly valid, but bond immunization can be approximated, which would be better than nothing. And at any rate it is a little galling to me to see Congressmen and old people themselves up in arms because they are apparently unaware that such a strategy exists.

* Image modified from one appearing at http://finance.ewu.edu/finc431/lecture/Chapter%2010.htm

Leave a Reply